The Quebec Act received royal assent on 22 June 1774. It revoked the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which had aimed to assimilate the French-Canadian population under English rule. The Quebec Act was put into effect on 1 May 1775. It was passed to gain the loyalty of the French-speaking majority of the Province of Quebec. Based on recommendations from Governors James Murray and Guy Carleton, the Act guaranteed the freedom of worship and restored French property rights. However, the Act had dire consequences for Britain’s North American empire. Considered one of the five “Intolerable Acts” by the Thirteen American Colonies, the Quebec Act was one of the direct causes of the American Revolutionary War (1775–83). It was followed by the Constitutional Act in 1791.

This is the full-length entry about the Quebec Act of 1774. For a plain language summary, please see The Quebec Act, 1774 (Plain-Language Summary).

In 1763, a century of imperial warfare in North America ended. Following the decisive British victory at the Plains of Abraham, France surrendered much of its North American territory to Great Britain with the Treaty of Paris. (See The Conquest of New France.) These lands included Île Royale (Cape Breton Island), Canada, and its holdings in the Great Lakes Basin and east of the Mississippi River (except New Orleans). The Royal Proclamation of 1763 brought these regions and their people into Britain’s North American empire.

Did you know?

The Treaty of Paris ended the Seven Years’ War between France, Britain and Spain. It marked the end of that phase of European conflict in North America, and created the basis for the modern country of Canada.

The Royal Proclamation aimed to assimilate the French-speaking population. English laws, customs and practices were established in the colony. It was hoped that a massive influx of English-speaking Protestant settlers would follow. The local French-speaking population was expected to assimilate in order to survive. The Proclamation also created an environment in which British merchants could gain a stranglehold on the colony’s economy, particularly in the fur trade.

In practice, however, things were very different. Since English-speaking immigrants were not coming en masse, Governor James Murray saw that assimilation was impractical. French speakers outnumbered English speakers and Murray depended on their co-operation to govern. Therefore, while he introduced English criminal law, he kept French property and civil law. According to historian Donald Fyson, French-speaking Catholics even held public offices.

Did you know?

In the five decades following the British Conquest of 1759-60, the English-speaking community in Quebec remained a small yet influential group. Because of this community’s relatively small size and the American Revolution brewing in the south, the ruling elite was reluctant to impose the British government’s official policy of anglicization and suppression of Catholicism that was being enforced in Ireland. They instead sought to win the loyalty of the French Canadian majority through measures of appeasement, notably the Quebec Act of 1774. This did not always sit well with the anglophone merchant class or the Anglican clergy.

In February 1774, Alexander Wedderburn, the solicitor general for England and Wales, began working on an act to replace the Royal Proclamation. He was assisted by Lord Dartmouth, the secretary of state for the colonies; Governor Guy Carleton; William Hey, the chief justice of the Province of Quebec; Lord Hillsborough, the former secretary of state for the colonies; Lord Mansfield, lord chief justice of the King’s Bench; and Attorney General Edward Thurlow.

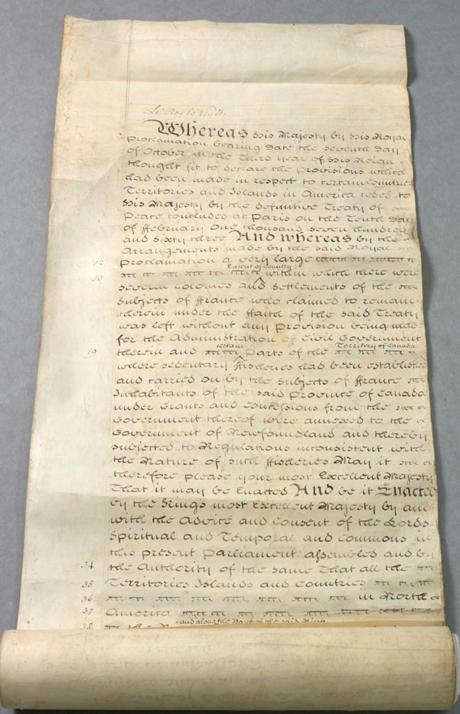

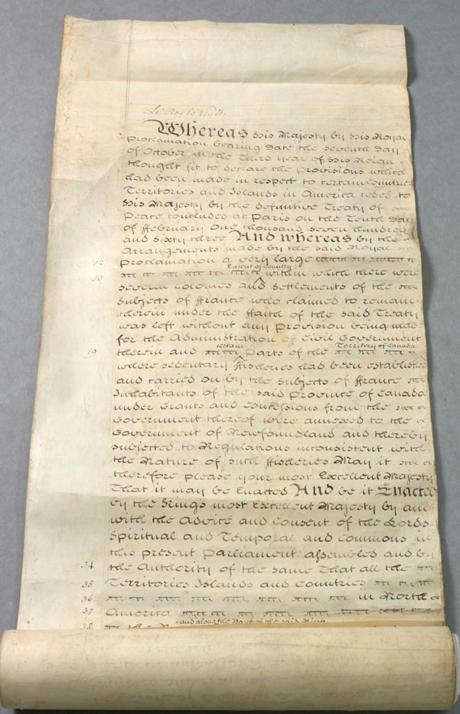

In June 1774, the Quebec Act was first passed by the British House of Commons. It was later adopted by the House of Lords. It received Royal Assent on 22 June 1774 and was put into effect on 1 May 1775. In many ways, the Act was shaped by the views of Murray and his successor, Guy Carleton. The slow arrival of English-speaking immigrants meant that colonial officials depended on local French-speaking colonists. Governor Carleton even warned officials in Britain that Quebec was “a province unlike any other, and its distinctive circumstances needed to be acknowledged.…”

As a result, Carleton argued that keeping French-Canadian customs was a much more practical option. He spent years convincing British officials to abandon their assimilationist policies. Given the growing tensions in the Thirteen Colonies, there was also concern that French Canadians might join a potential revolt. It was imperative that Britain gain their loyalty.

The Quebec Act once again divided the North American territory. The Province of Quebec was greatly enlarged. It was no longer limited to the St. Lawrence River valley. Its borders expanded to include Labrador, Anticosti Island, the Magdalen Islands and a large area to the west of the Thirteen Colonies. This included what would become Southern Ontario, the disputed territory of Ohio, Michigan and Indiana, and even parts of modern-day Wisconsin, Illinois and Minnesota. The region also included what was then called the “Land of the Indians.” The Royal Proclamation had recognized it as Indigenous reserves. The proclamation had banned European settlement on this territory. According to Alan Taylor, the idea was that “Quebec’s authoritarian government” could better prevent settlers and land speculators from the Thirteen Colonies from moving to this land.

The Quebec Act was intended to appease French Canadians and to gain their loyalty. First and foremost, the Act allowed them to freely practice Roman Catholicism. This was in stark contrast to how the British government had handled similar situations. For the previous 200 years, it had adopted anti-Catholic approaches, particularly in Ireland. But it recognized Quebec’s distinct realities and adopted a different attitude. With freedom of religion, French-speaking Catholics were no longer barred from running the affairs of the colony. They were only required to swear an oath of allegiance to the king, which made no mention of one’s religious affiliation (unlike under the previous Test Act).

Though English criminal law was retained, the Act restored French civil law. This meant that the Roman Catholic Church could now legally collect tithes. The seigneurial system was also re-established. While the seigneurs and church officials were undoubtedly happy, French-speaking inhabitants were less pleased about having to pay seigneurial dues and taxes. The Act also revoked every ordinance that had been passed between 1764 and 1775. As stated by the Royal Proclamation, legislative authority could only be held by the governor, his council, and the assembly. And since an assembly was never created, colonial authorities did not have the power to impose taxes or duties.

To English-speaking colonists, especially the men of the “British Party,” the Act was not something to celebrate. These men — most of whom were merchants living in Montreal and Quebec City— wanted to assimilate the French-speaking population. They hoped to turn the colony into a proper British colony. They wanted the English common law system and freehold tenures instead of the seigneurial system. They also wanted an elected assembly under the control of the British Party. They argued that only English-speaking Protestants should be able to vote or hold public office. They even petitioned — unsuccessfully — in favour of this.

British officials rejected these demands. They feared that a British-dominated assembly would cause tensions within the colony. Historian Alan Taylor concluded that “Quebec presented a paradox where a British minority resented that imperial officials protected the culture and law of the French majority.” Instead, a Legislative Council of 23 would be appointed by the Crown. It would govern the colony with the governor. Nevertheless, the expansion of the colony’s territory surely pleased many British merchants, as it significantly increased their commercial reach.

Perhaps the most important consequence of the Quebec Act was the American Revolutionary War (1775–83). The Quebec Act was very unpopular among settlers in the Thirteen Colonies. They thought it was a kind of “British Authoritarianism.” It was considered one of the five “intolerable acts” passed by Britain in the lead-up to the revolution.

One month before the Quebec Act passed, the British Parliament approved a series of acts that angered people in the Thirteen Colonies. These included the Boston Port Act, an Act for the Impartial Administration of Justice, the Quartering Act, and the Massachusetts Government Act. These “intolerable acts” were condemned by the American colonists as unjust and despotic. The Boston Port Act, for instance, shut down the city’s port until locals paid for the tea that was destroyed during the famous Boston Tea Party. The newly amended Quartering Act now allowed authorities to lodge British soldiers in private homes. And the Massachusetts Government Act turned the elected colonial council into an appointed one. It also banned all town meetings that took place without the consent of British officials.

In this context, the Quebec Act was just another “intolerable act.” John Adams, for example, was a supporter of the American Revolution. He served as a delegate for Massachusetts during the Continental Congress. He said that the Act was “dangerous to the Interests of the Protestant Religion and of these Colonies.” American colonists were especially opposed to the fact that the British Crown was favouring French-speaking Catholics over its own Protestant colonists. Most were furious that they were banned from settling in the Ohio valley. Some even argued that many had given their lives to free this land from the control of French Catholics. The New York Journal cried out that, “the Savages of the wilderness were never expelled to make room in this, the best part of the continent, for idolaters and slaves [French Canadians].” Others also feared that the Act was “a premeditated Design and System, formed and pursued by the British Ministry, to introduce an arbitrary Government into his Majesty’s American Dominions.”

The Quebec Act not only created more tension in the Thirteen Colonies. More importantly, it broke the bond between the colonists and the British monarch. According to historian Vernon P. Creston, this “fatally undermined the popularity of the most recognizable, and cherished, symbol of the British Empire’s authority in the American colonies.” American colonists even used the Act to justify “physical resistance” against the British. They saw it as “proof that their king could no longer be trusted.” The Act had shown how tyrannical and corrupt the Crown had become. Many American colonists felt betrayed. They believed it was their duty to “resist such sweeping attacks on their liberty.”

During the American Revolutionary War, two invasion forces were sent to Canada to recruit locals in the fight against the British. They were led by Colonel Benedict Arnold and General Richard Montgomery. These attacks failed due to difficult conditions, a lack of supplies and a lack of support from the local population. (See American Revolution – Invasion of Canada.)

The Quebec Act was followed in 1791 by the Constitutional Act. Much had changed since 1774. Thousands of Loyalists arrived in the Maritimes and in the Province of Quebec and settled north of the Great Lakes. After arriving in a British colony that had French property and civil laws and lacked British institutions, these Loyalists began pressuring British officials to establish English common law and a proper legislative assembly. On the other hand, French Canadians feared that the increasing number of Loyalists would result in the loss of the rights they had gained with the Quebec Act.

The 1791 Constitutional Act was a compromise. The Province of Quebec was divided into the colonies of Upper Canada and Lower Canada. Upper Canada, where most Loyalists had settled, adopted English common law. Lower Canada, where most French Canadians lived, kept French property rights and all of the privileges that French Canadians had gained in 1774. Both colonies also benefited from political representation with the creation of separate, elected Legislative Assemblies.